Articles & Research

Brain’s ‘Traffic Directors’: Neurons That Keep Us Focused on Tasks

Summary: Researchers have illuminated how our brain maintains focus amidst distractions.

Their study identifies “visual-movement” neurons in the lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) that use coordinated activity called “beta bursts” to suppress distracting stimuli and ensure attention remains on rewarding tasks. This discovery gives a deeper understanding of cognitive focus and offers insights into disorders like ADD and OCD.

Key Facts:

1. “Visual-movement” neurons in the LPFC help the brain to suppress distractions and focus on tasks.

2. These neurons produce coordinated “beta bursts” which, when strong, help subjects to remain focused.

3. This study provides deeper insights into “top-down” control, where attention is directed towards a goal while ignoring distractions.

Trying to finish your homework while the big game is on TV? “Visual-movement” neurons in the front of your brain can help you stay focused, according to a new study from neuroscientists in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

In the study, published recently in Neuron, the scientists sought to illuminate the neural mechanism that helps the brain decide whether to focus visual attention on a rewarding task or an alluring distraction.

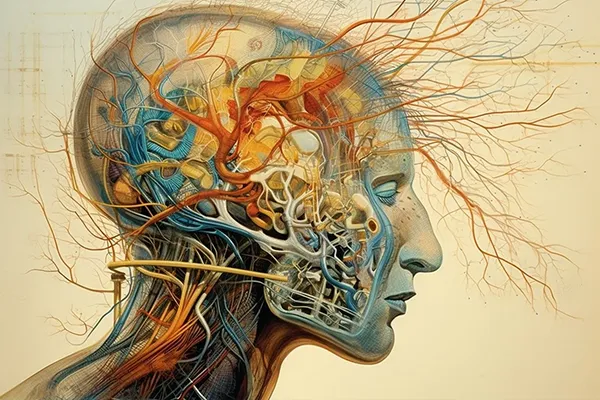

The researchers also observed that visual-movement neurons in the LPFC fired together at the same frequency, called “beta bursts” during periods of focus (when ignoring visual distractions and completing tasks). Credit: Neuroscience News

By analyzing neuron activity in animal models as they faced this kind of attentional conflict, the researchers discovered that a pattern of coordinated activity called “beta bursts” in a set of neurons in the lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC)—a section in the front of the brain responsible for motivation and rewards—appears to have a major role in keeping attention task-focused, essentially by suppressing the influence of the distracting stimulus.

“Our research suggests that while all brains have the ability to focus on a rewarding task and filter out distractions, some are better at it than others,” said senior author Bijan Pesaran PhD, the Robert A Groff II Professor of Neurosurgery at Penn Medicine.

“By understanding how our brains process rewarding stimuli, we hope to be able to also understand failures to do so in a variety of cognitive and psychiatric disorders, including attention deficit disorder, schizophrenia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.”

Humans and other large mammals can tune out distractions to keep their attention focused on actions that further goals. This is called “top-down” control, in which attention is directed towards a task with the intention of accomplishing a rewarding goal.

Large mammals like primates also have brain circuitry that automatically redirects their attention based on incoming sights and sounds and other “salient” sensory stimuli, otherwise known as “bottom-up” control. How the brain suppresses such distractions to keep attention focused on a goal-related task has never been fully clear, until now.

In the new study, the researchers sought to understand what directs attention to some stimuli, but suppresses others in more detail. Using animal models, researchers recorded how activity in the LPFC shifts while completing a task while being presented with visual distractions.

The neuroscientists found strong evidence that one specific type of LPFC neurons, called visual-movement neurons, direct attention towards either the rewarding shape or the distracting one.

The researchers also observed that visual-movement neurons in the LPFC fired together at the same frequency, called “beta bursts” during periods of focus (when ignoring visual distractions and completing tasks).

When these beta bursts occurred in the moments before the visual stimuli were presented, subjects were far more likely to ignore the visual stimuli and complete the task. In contrast, when the beta bursts were weak or absent before visual stimuli were presented, subjects were more likely to move their attention to the bright but unrewarding shapes.

“This suggests to us that the beta-bursts originate in a network of visual-movement neurons, and act as ‘traffic directors’ for the neurons that process different visual stimuli,” said first author Agrita Dubey, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Pesaran laboratory.

“It also suggests that focusing on a rewarding task takes a great deal of energy, and that it may be something that can be improved, especially in individuals with attention deficits.”

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (F32-MH100884, T32-EY007158, R01-NS104923, UF1-NS122123) and the Department of Defense (MURI W911NF-16-1-0368).

About this neuroscience research news

Author: Kelsey Odorczyk

Source: University of Pennsylvania

Contact: Kelsey Odorczyk – University of Pennsylvania

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Closed access.

“Top-down control of exogenous attentional selection is mediated by beta coherence in prefrontal cortex” by Bijan Pesaran et al. Neuron

Abstract

Top-down control of exogenous attentional selection is mediated by beta coherence in prefrontal cortex

Highlights

· Visual-movement neurons encode exogenous and endogenous attentional selection

· Coherent beta activity selectively modulates mechanisms of exogenous selection

· Beta activity suppresses exo-selection when in conflict with endo-selection

· Beta-activity-mediated mechanisms selectively inhibit visual-movement neurons

Summary

Salience-driven exogenous and goal-driven endogenous attentional selection are two distinct forms of attention that guide selection of task-irrelevant and task-relevant targets in primates. Top-down attentional control mechanisms enable selection of the task-relevant target by limiting the influence of sensory information.

Although the lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) is known to mediate top-down control, the neuronal mechanisms of top-down control of attentional selection are poorly understood.

Here, we trained two rhesus monkeys on a two-target, free-choice luminance-reward selection task. We demonstrate that visual-movement (VM) neurons and nonvisual neurons or movement neurons encode exogenous and endogenous selection. We then show that coherent beta activity selectively modulates mechanisms of exogenous selection specifically during conflict and consequently may support top-down control.

These results reveal the VM-neuron-specific network mechanisms of attentional selection and suggest a functional role for beta-frequency coherent neural dynamics in the modulation of sensory communication channels for the top-down control of attentional selection.